Exiting the building, I exhaled. It finally happened. I finally obtained my Colombian citizenship.

The feeling of closure I had leaving the Republic’s consulate at 550 Broad Street, Newark was strong; aside from the fact that I had just lost three precious hours watching bureaucrats do their job.

This was my first step in establishing myself as a Latin American citizen, a connection I had to fight for. Endless back-and-forths with my parents and other community friends tried to stop this, but the long-lost connection exists. I am complete.

Just as I defied conventions on this issue, I hope to do so again on another one: I, the child of immigrants to the United States, will leave the United States. For a time, at least.

My father immigrated in 1986 as his native El Salvador was being ravaged by war. My mother, through whom I obtained my citizenship, came four years later as an economic migrant. Almost forty years later, the conclusion they and many other immigrants of their generation have come to is profound and simple: This level of comfort could not have been possible had we stayed at home.

Many younger immigrants believe that as well, and it’s broadly true. The U.S. sits high in many rankings such as that of the OECD and the UN’s Human Development Index.

Our country has its “land of milk and honey” reputation smeared across the globe’s imagination. Even through our educational and pop culture systems we romanticize the “immigrant experience.” Hell, even the MAGA set is sometimes willing to make exceptions.

But putting aside the gut-wrenching events unfolding in our country right now, the American Dream is not easy to achieve. Immigrant and native-born Americans of my generation face challenges unimaginable to our Boomer and Gen-X parents back in the day.

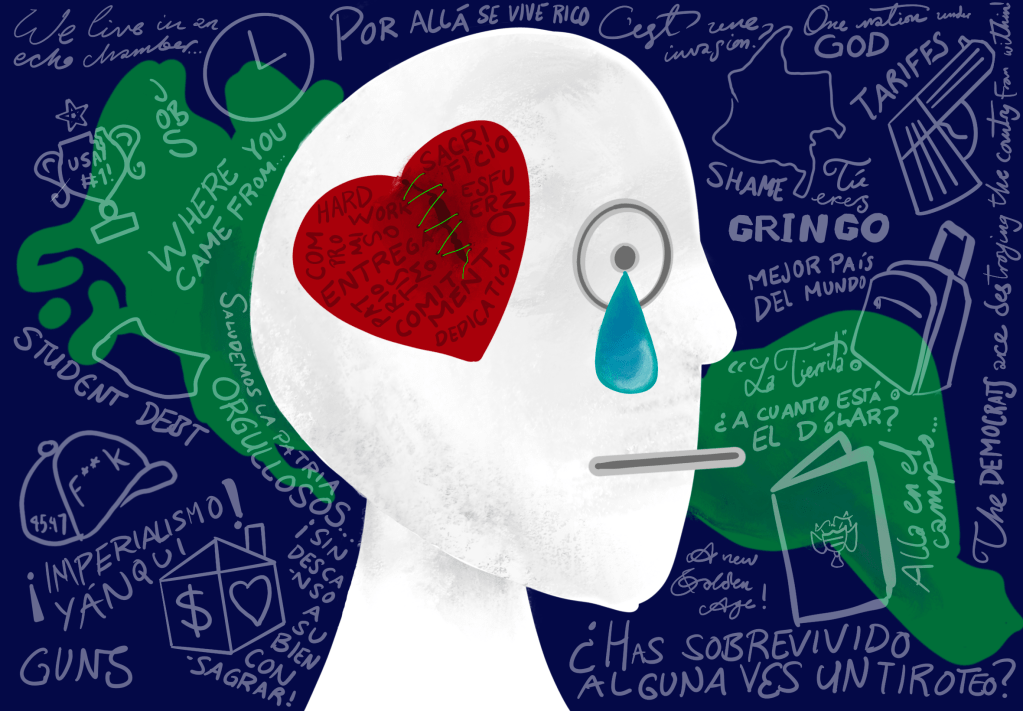

We can’t afford a house. We can’t get a job. We can’t get around easily on public transportation. We can’t trust people to own guns. We can’t get sick. We can’t even pay off student debt. Wait — Did I mention that’s not a thing elsewhere?

I admit — These are all boilerplate progressive complaints, but is this ultimately what our parents wanted for us, themselves, or anyone? Do you have to be progressive to hold any of those positions?

“But Christopher” — says Immigrant Boomer X — “Things are much worse where we come from.”

I’ve had to wrestle with this million-dollar question for a while now, and I get it. Things worked out for you much better here and I am glad for it. I am particularly glad and grateful for my parents’ efforts which led me to the aforementioned comfort and possibilities I grew up with.

However, I beg to differ. People who think like this, immigrant and native-born alike, are stuck in a false dichotomy between the rich, prosperous, free North and the backward Global South. They don’t tend to ask themselves, “Why is the global south like this?” It just is. I don’t think (or hope) I have to go over things such as the Banana Wars or Operation Condor.

Then there’s the whole matter of identity. Do I feel American? What does it mean to be American? Can nationalism be just healthy patriotism? How am I supposed to feel about the history between North and Latin America? Supremacism? Denial?

I tend to ask relatives and Latin America-based friends to stop referring to me as “gringo.” “Gringo” is not who I am. “Gringo” is the tourist in shorts and sandals. “Gringo” is the businessman on a trip getting ready for a meeting in the capital.

The term, formerly attributed to the Mexican American War, is now understood to have been a corruption of griego, or “Greek.” It implies no connection to the land or the people; it is like calling someone an “alien.”

Norteamericano is fine. Estadounidense is okay. Americano a little less so. But definitely not gringo.

As our political adventure with MAGA progresses, many of my foreign relatives and friends often ask me how I feel about it. At times, it feels embarrassing to even have to answer.

Then there are also the episodes of more snarky and mean-spirited jokes. At World Youth Day 2023 in Lisbon, I had the honor of carrying the Stars and Stripes for my university’s delegation. One day, a French teenager asked me as if “this was an invasion.” That same day, I chatted for a while with two young Spaniards in the subway after they casually asked me if I had ever survived a gun massacre.

Annoying as this might be for someone who would have to deal with it frequently, it does force more questions onto my already beleaguered mind: What have I been missing out on? Why was I never encouraged in high school history class to put myself in the foreigner’s shoes? Why did our teacher spend some classes railing on about how the Democrats are destroying the country from within?

Why did they deny me my Colombian citizenship in the first place?

I admire our American ideals of freedom, entrepreneurship, optimism, and democracy as a measure against tyranny. But are those beautiful ideals what force me to carry around my passport? How can the American dream — despite everything — not be for me?

We as young people are not wedded to what our parents built for themselves. We have the right to demand a system to bring us to their relative level of comfort and keep it for our own children. Comparing systems by just looking at the extremes forces you into the dichotomy.

Yes, I am a proud American. But I want some fresh air. Guess I’ll have to go find it.

Follow-up note: This personal essay was published on April 25th, A symbolic date in the history of immigration and the world. Read my follow-up here.

Leave a comment